Such is the title of a new book published by

Die Andere Bibliothek concerning "Goethes unbekannter Grossvater" (as per the subtitle). For those who like archival research, and that includes me, this is a book for you. The authors are Heiner Boehncke, Hans Sarkowicz, and Joachim Seng, all respected Goethe scholars. (For German reviews, go to

Perlentaucher). The subject is the paternal grandfather, Friedrich Georg (1657–1730), who died long before young Wolfgang came into the world, but whose considerable fortune allowed the Goethe family to live so comfortably in Frankfurt. The French-accented last letter of the name comes from his residence in the leading French textile center, Lyons.

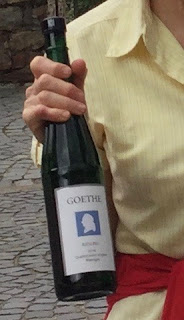

Friedrich Georg is a somewhat shadowy figure, in contrast to the maternal grandfather, Johann Wolfgang Textor, one of the leading citizens of Frankfurt and a member of the city's oligarchy. Goethe mentions grandfather Textor in his autobiography, but deals with Friedrich Georg very quickly, not even mentioning his name. Of this forebear, Nicholas Boyle writes only that he was "a Thuringian tailor of peasant stock, who, after years of wandering that had taken him for a time to Paris and Lyons," settled in Frankfurt after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes (1685). In Frankfurt, he proceeded to make a fortune with his tailoring and through his second marriage to the widow of an innkeeper. It was the hundreds of barrels of wine from the inn that made Caspar Goethe a rich man. The authors of

Monsieur Göthé spell out the details of his inheritance: approximately 12,000 liters of wine flowed into the cellar of the house on Hirschgraben. They go on to say that young Goethe came into the world with an immense "Weinvorrat, der gepflegt, umgefüllt, mit Kennerschaft und in ziemlich großen Mengen getrunken wurde," especially of the premier Mosel wines of the years 1706, 1719, and 1726, which Wolfgang's mother affectionately referred to as "die alten Herren."

Friedrich Georg was born in a Thuringian town, Artern, and indeed all the previous Göthes (so spelled) lived and died in that area, in towns with names like Berka and Kannawurf, not far from Weimar. The first one recorded in

Monsieur Göthé is a Hans Gothe, a stone carver, born in 1500. Goethe may have known of this family origin, but appears never to have been interested in researching it in his Thuringian travels. The authors are of the opinion that Wolfgang, following his father's

lead, obscured his paternal grandfather's working-class origins by

ignoring them, especially in the autobiography.

They discuss the episode in the autobiography (book 2), when Goethe was very young and attended school. He reports of the strict discipline of the teachers and of the necessity of enduring the physical punishments they meted out, since to respond would have brought more of the same. But because he flaunted his endurance, several of his classmates, rough, less genteel boys, tested him, attacking him with switches. He managed to turn the tables on them, however, and defend himself. Another time, he was taunted by some boys who suggested that his paternal grandfather could not possibly have made so much money as an innkeeper and that Goethe's father was actually the illegitimate son of a man of rank ("der Sohn eines vornehmen Mannes") who had talked the innkeeper in pretending to be the father.

Whether this account in the autobiography is a true version of what happened, Goethe goes on to report of the strange effect this rumor had on him ("eine Art von sittlicher Krankheit"). It did not offend him to be thought to be the grandson of a noble personnage, even if illegitimately so. In fact, he was quite flattered. This is where he references grandfather Friedrich Georg (though not by name), whose portrait

had once hung in the drawing room of the old house but was

now stored in the attic of the new one! So, in the absence of knowing nothing about this grandfather, young Goethe started looking at paintings of famous men and seeking resemblances to himself. When visiting friends in Frankfurt with high connections and with portraits of famous men decorating their walls, he would study them carefully to see if he could discover any similarities with himself or his father. Goethe's own estimation was that his self-conceit was fueled by these speculations, and not necessarily in an estimable way.

This particular account enraged Goethe critic

Ludwig Börne (1786–1837) who lambasted Goethe for mentioning only that he was the grandson of Schultheiss Textor, which allowed him to attend the imperial coronation. Börne continued "Ein Kind ehrbarer Eltern entzückte es ihn, als ihn einst als Knabe ein Gassenbube Bastard schalt, und er schwärmte mit der Phantasie des künftigen Dichters, wessen Prinzen Sohn er wohl möchte seyn. So war er; so ist er geblieben."

Even Heinrich Heine weighed in on this episode of Goethe's childish pretensions, while thoroughly mixing up the two grandfathers. Frankfurt's chief magistrate thereby became the father of Caspar, while Goethe was criticized for not mentioning with one word that his mother's father was a "ehrbares Flickschneiderlein auf der Bockenheimer Gasse" who repaired "die alten Hosen der Republik."

To be continued. Stay tuned.