On this date in 1777 Goethe received news of the death of his sister

Cornelia the previous week, on June 8, four weeks after the death of her

second child. His diary entry concerning the news is brief, with

"zurück" referring to his return to Weimar from Kochberg, the von Stein

estate:

früh zurück. Brief des Todts m. Schwester. Dunckler zerrissener Tag.

One

assumes that he related the news to the duke, but the only document

concerning his immediate reaction, a letter to Charlotte von Stein on

the same day, is terse:

Um achte war ich in meinem

Garten fand alles gut und wohl und ging mit mir selbst, mit unter lesend

auf und ab. Um neune kriegt ich Brief dass meine Schwester todt sey. --

Ich kann nun weiter nichts sagen.

Every study I have

seen of Goethe's sister stresses the close relationship between Cornelia

and Wolfgang, who was one year older. (There had been another brother

who survived early childhood, but only to the age of seven.) They were

both educated at home, having many of the same lessons and teachers. His

letters to her from Leipzig, where he enrolled as a student at the age

of sixteen, reflect the bookish atmosphere in which they were raised.

These letters display the pedagogical bent that was lifelong. As the

elder sibling, he is always instructing her, especially on how to write a

proper letter. This instruction itself reflects what he was learning at

the time, as he attended the classes of Christian Fürchtegott Gellert, who besides being one of the most popular German writers of the 18th century, penned a letter-writing style manual: Briefe, nebst einer praktischen Abhandlung von dem guten Geschmacke in Briefen

(Letters, together with a practical treatise on good taste in letters,

1751). Letter-writing was an absorbing interest in the 18th century, as

can be seen in the epistolary novels of Richardson and Rousseau. Germans

learned from these writers, and carried on the tradition, with Goethe's

The Sorrows of Young Werther being one of the most exemplary.

Goethe

himself, however, rarely displayed such an outpouring of personal

emotion in his letters. We know of the effect on him of grief, in the

case of Cornelia's death, by what he did not put into words. A further

diary entry, the next day, is very succinct: "Leiden und Träumen."

That says it all, but he did write to his mother later in the month, in

which he writes of the way that the good fortune he is currently

enjoying in Weimar makes Cornelia's death more painful. And then a very

interesting observation concerning the difference between recovery

from physical pain and from grief:

Ich kan nur menschlich fühlen, und lasse mich der Natur die uns heftigen Schmerz nur kurze Zeit, trauer lang empfinden lässt.

A longer letter to his mother in November contains a beautiful, image-rich passage describing his relationship to his sister (and below it my paltry translation):

Mir

ists als wenn in der Herbstzeit ein Baum gepflanzt würde, Gott gebe

seinen Seegen dazu, dass wir dereinst drunter sizzen Schatten und

Früchte haben mögen. Mit meiner Schwester ist mir so eine starcke Wurzel

die mich an der Erde hielt abgehauen worden dass die Äste, von oben,

die davon Nahrung hatten auch absterben mussen.

(It seems to me as if in autumn a tree had been planted, to which God gave his blessing so that we might one day sit in its shadows and have fruit from it. With my sister, it is as if a strong root that held me to the earth has been torn up, so that the branches above above that had their nourishment from it also had to die.)

Photo credit: Rain Forest Alliance

Tuesday, June 16, 2020

Sunday, June 14, 2020

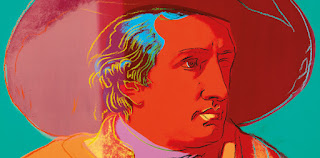

Goethe in Fiction

I have a feeling that there is a large topic on the subject of the title of this post. Suffice it for today simply to post here a passage in English translation from Ingrid Noll's 1993 novel Der Hahn ist tot (English: Hell Hath No Fury). The reason for the different typeface below is that I have copied the passage from a great blog called Clothes in Books. Please go to that link for observations on the passage by Moira Richmond, the host of Clothes in Books.

I had a bath, washed my hair and blow-dried it. Witold wouldn’t be coming in the morning, since he had to be in school. But as to whether he would arrive immediately after lunch or not until later, I could only guess. From two in the afternoon, I was waiting, in my silken pyjamas; I put away my tea-cup, fetched it out again, cleaned my teeth once more. By six I was extremely edgy....

At last, at eight, he arrived…

‘Come on,’ he said, ‘don’t hang around in the kitchen, lie down on the sofa. I’ll stay with you for a few minutes.’

In my silk nightwear, I tried to assume as decorative a pose as possible, a bit like Tischbein’s painting of Goethe in the Campagna.

‘I looked awful yesterday, you must have been disgusted by the sight of me,’ I murmured.

‘Don’t worry yourself, that’s how everybody looks when they’re in a bad way.’ Witold really did seem to pay precious little attention to my appearance.

I had a bath, washed my hair and blow-dried it. Witold wouldn’t be coming in the morning, since he had to be in school. But as to whether he would arrive immediately after lunch or not until later, I could only guess. From two in the afternoon, I was waiting, in my silken pyjamas; I put away my tea-cup, fetched it out again, cleaned my teeth once more. By six I was extremely edgy....

At last, at eight, he arrived…

‘Come on,’ he said, ‘don’t hang around in the kitchen, lie down on the sofa. I’ll stay with you for a few minutes.’

In my silk nightwear, I tried to assume as decorative a pose as possible, a bit like Tischbein’s painting of Goethe in the Campagna.

‘I looked awful yesterday, you must have been disgusted by the sight of me,’ I murmured.

‘Don’t worry yourself, that’s how everybody looks when they’re in a bad way.’ Witold really did seem to pay precious little attention to my appearance.

Tuesday, June 9, 2020

Goethe and Trade: Correction

|

| Global Trade Map |

In any case, here follows the earlier post with my error regarding the omission in the Apprentice novel. What still stands, of course, is what I wrote concerning Goethe's understanding of trade and commerce when he dictated the Urmeister.

FIRST ITERATION OF "GOETHE AND TRADE" (ON JUNE 9, 2020)

My summer reading includes Goethe's earliest version of the Wilhelm Meister saga, which I am beginning to think can be characterized as a roman fleuve, in the sense that Roger Shattuck discusses that term in connection with Proust's seven-volume novel. This early version, entitled by scholars Wilhelm Meisters Theatralische Sendung, was dictated by Goethe in the early 1780s, but the manuscript was not discovered until 1909, after which it appeared in published form. Whether Proust knew of this early version, he was familiar with Elective Affinities and the Wilhelm Meister novels. (The collection Marcel Proust on Art and Literature, translated by Sylvia Townsend Warner, contains an essay by Proust on Goethe.)

The topic of trade occurs in the 8th chapter of part 2 of the Theatralische Sendung, during a discussion between Wilhelm and his brother-in-law Werner. I think we are supposed to assume that Werner is a prosaic sort, attuned only to the family business, but, Wilhelm having suffered a nervous breakdown over the love affair portrayed in part 1, Werner has been attempting to build him up again. In the preceding chapters, he has spent many an hour listening to Wilhelm discoursing on the theater and on his writing efforts.

In a similar spirit of enthusiasm and in an attempt to draw Wilhelm's thoughts in a new direction, Werner portrays to him the charms of trade and commerce. It is astonishingly clear sighted concerning the effects of capitalism and imperialism. This discussion is not included in the eventual canonical Wilhelm Meister saga. For those interested but whose German may not be up to it, I recommend pasting the following into Google Translate.

Wirf einen Blick auf alle natürliche und künstliche Produkte aller Welteile, siehe wie sie wechselweise zur Notdurft geworden sind; welch eine angenehme geistreiche Sorgfalt ist es, was in dem Augenblick bald am meisten gesucht wird, bald felt, bald schwer zu haben ist, jedem der es verlangt, leicht und schnell zu schaffen, sich vorsichting in Vorrat zu setzen und den Vorteil jedes Augenblickes dieser großen Zirkulation zu genießen. ...

Es haben die Großen dieser Welt sich der Erde bemächtiget und leben in Herrlichkeit und Überfluß von ihren Früchten. Das kleinste Fleck ist schon erobert und eingenommen, alle Besitztümer befestiget, jeder Stand wird vor das, was ihm zu tun obliegt, kaum und zur Note bezahlt, daß er sein Leben hinbringen kann; wo gibt es nun noch einen rechtmäßigern Erwerb, eine billigere Eroberung als den Handel?

There is much more of Werner's comments in this chapter, but the above is a small taste.

I have often thought that Goethe's ideas on world literature, dating from the 1820s, were grounded in a recognition of the global spread of trade and commerce -- in fact, I have published an essay on this subject and also written about it on this blog, including this post and also here -- but I was thrilled to come across his early portrayal of the subject.

Image credit: Financial Channel

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)