Consider the following a book review of a very small volume (47 pp.) of translations of poems by Goethe entitled

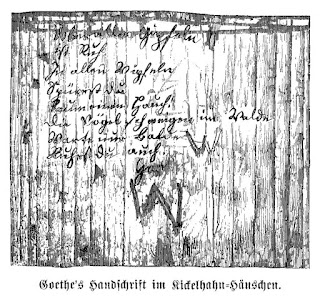

Nightwalker’s Song. I saw an ad for the book in the London Review of Books and wrote the publisher, Arc Publications, expressing my interest in writing about it for the blog. Arc kindly sent me a copy. The translator is John Greening, and the selection of poems, with German and English texts, is from Goethe’s early and middle years, from one of Goethe's most famous poems, “Wandrers Nachtlied” (

Über allen Gipfeln; 1780) to the sonnet “Natur und Kunst” (1800; publ. 1809). In between are poems that have been a favorites of poets (among others, Christopher Middleton, David Luke, and David Constantine) who have tried their hand at reproducing Goethe’s rhythms, structures, and vocabulary : “Willkommen und Abschied,” “Prometheus,” “Harzreise im Winter,” “Römische Elegien” (I, V, XIV, XX), “Nähe des Geliebten,” “Der Zauberlehrling,” and “Faust im Studierzimmer.” Each poem is prefaced with a few lines of background.

John Greening himself is a considerable poet and writer about poetry. His poetry, from what I have gleaned online, can be recondite, at least for this American reader. (A collection of his poetry for “American readers” has been published by Baylor U Press.) Take a poem entitled “

Heath XXIX,” from a collection “about an airport and its surrounding area.”

The collection, a joint project with the poet Penelope Shuttle, “merges voices on the impact of Heathrow Airport on

Hounslow Heath, and the things we’ve lost as a result of it.” It turns out the heath on which the airport is located has a long history in the west and southwest of Britain. The venerable Bede is among the ghosts of this history, along with the Church of St. Mary the Virgin. Herewith the opening lines:

|

Richard Wilson, Hounslow Heath (ca. 1770)

|

Twenty-four thousand times in any year, lightning strikes

and kills. On the Heath, the timber shells, like bony Flemish spires,

point heavenwards in warning. The stags take note and bow their heads

at the sky’s first challenge, or hurl a bellowing peal back in defiance.

Besides his many books of poetry, Greening has published essays on poetry. One subject of interest is the poets of World War I. He is not a scholar of German literature, but he did spent time as a student in Mannheim, and even spent a summer in residence month living in the Heinrich Böll cottage in Dugort, Achill Island. In one of his essays, Greening addresses the issue of being a “European,” in which he takes on an “indigestible” essay by T.S. Eliot and considers his own bona fides on the issue. In this connection, he has translated Georg Heym, Georg Trakl, Ernst Stadler and August Stramm, “poets who wrote about (or anticipated, in Heym’s case) the First World War.”

I am guilty of not having given much thought to the subject of translation, although, like many of us, any learning I posses is a result of having read works in translation, both in the Christian and the Western classical tradition — and in recent decades literature from non-Western parts of the world. Goethe himself was of course a beneficiary of all that inheritance, even as he was more fluent in Greek and Latin, not to forget French and Italian, than I ever was — not to forget being

bibelfest. Whether it be the evidence of the

Roman Elegies or the

West-East Divan, Goethe certainly knew the value of this inheritance. In turn, Goethe’s language had an immense influence on the German language going forward, similar, as it is said, to the King James version of the Bible.

German is an intransigent language to translate, even in prose. For those who do know German, I suspect their interest in translations of Goethe’s poetry will be attuned to issues of structure, rhythm, rhymes and meter, vocabulary, and the like, all of which render an inimitable musicality. That said, there is simply no way that English can match Goethe’s German, especially his musicality. For those who don’t know German, there remain some who might be interested in what the poetry has “to say.” For those potential readers, I suspect it is the content of his poetry, the “spirit,” that would be of interest. This has been called a “culture to culture” translation.

While aware of the semantic differences between German words and their English equivalents, Greening has sought to reproduce Goethe’s original meters. From my recent experience working on a translation of a German novella, rendering the different emotional expression that words convey is exceptionally frustrating. And German has these strange word formations, especially Goethe’s German.

Of course, a translator must render that content in a readable idiom. Here are a few lines from a stanza of “Willkommen und Abschied,” followed by Greening’s translation. The lines present a simple picture, easy to understand. We’re not talking Klopstock here. Someone with a couple years of German could recognize the different semantic values of the German vocabulary as well as the rhyme.

Der Mond von einem Wolkenhügel

Sah kläglich aus dem Duft hervor,

Die Winde schwangen leise Flügel,

Umsausten schauerlich mein Ohr.

Die Nacht schuf tausend Ungeheur,

Doch frisch und fröhlich war mein Mut:

In meinen Adern welches Feuer!

In meinem Herzen welche Glut!

The moon looked sadly through a veil

of cloud, the winds began to beat

soft whirring wings about me, till

my ears could no more bear, the night

revealed its thousand horror masks.

And yet my fiery spirits cheered,

hotly defying such grotesques,

from heart and veins the lava poured.

Greening has abandoned Goethe’s rhyme, and also the definitiveness of Goethe's couplets. In the process, however, the enjambment of the first five lines of his version intimates the flow of loving feeling between the speaker and his beloved. But, then, in the final three lines of the stanza, Greening abandons enjambment and follows Goethe: three stand-alone lines echo Goethe’s defiant response to the effect of the dark night and its accompanying grotesques.

.jpg) |

| Ernst Barlach, Harzreise im Winter (1924) |

|

This is only one small example of the many choices Greening has made, which he discusses in his introduction. I particularly liked his recommendations of G.H. Lewes’ biography of Goethe as conveying “the full scope of Goethe’s genius” (and as also the most entertaining book about Goethe) for English readers. Many non-specialists may feel inspired by the tale of his own path to Goethe, while Greening's translations also remind us scholars about what real poets appreciate about Goethe. Greening, for instance, wishes more attention were paid to the free-verse “Harzreise im Winter”: “It would be good to encounter this poem as often as one finds modern versions of, say, Rilke’s ‘First Duino Elegy.’” My favorites among his translations are “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice,” “Faust in His Study,” and “Nature and Art.”

Images:

The Tate;

Art Net

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)