Lately I have been going through books long laid aside in connection with Goethe, among them a book of essays by George Eliot in which one finds "Three Months in Weimar." After reading the essay, I decided to discuss it on the blog and, in preparation, I started looking for images. I typed "George Eliot in Weimar," hoping for some interesting images of Weimar in the year 1854, when Eliot accompanied George Lewes there. Lewes was collecting material for the biography of Goethe on which he had been working. Much to my surprise, I came across a site so titled:

George Eliot in Weimar. It appears to be a one-off sort of blog, posted on successive days in January 2019, commemorating Eliot's 200th birthday. There are ten "episodes," with each post excerpting highlights of the visit to Weimar, either a portion from the essay or from Eliot's journal or letters: Arrival at Weimar, Hotel zum Erbprinzen, Kaufstraße, The Goethe Haus, The Schiller Haus,Theatre with Goethe-Schiller-Denkmal, The Stadtschloß, The Altenburg, The Ilm Park with Goethe’s Garden House, The Garden House – Guest Book, The Belvedere Schloß, The Ettersburg, The Tiefurt Schloß, Bad Berka, The Kickelhahn Hut, Leaving Weimar. The blog includes audio recordings of readings from the writings.

Since Eliot was traveling with a man who was not her husband, the essay itself is not very forthcoming about who she is with or why she is even there. It seemed like a piece of travel journalism, and, except for a few places (the visit to Schiller's house), not very fascinating. The blogger at the "George Eliot in Weimar" website, however, has made things more interesting, beginning with asserting that the journey to Weimar represented a kind of honeymoon for the two Georges. Thus, entries from her "recollections" mention George Lewes by name ("George"). The following is a nice passage not included in the essay.

"Another delightful place to which we often walked was Bercka

(sic),

a little village, with baths and a Kur-Haus seated in a lovely valley

about six miles from Weimar. The first time G. went I was obliged to

stay at home and work, and when he came back he merely said that the

place and the walk to it were pretty, and brought me a bunch of berries

from the mountain ash as a proof that he had thought of me by the way.

He wished to ménager (prepare) a surprize for me by the moderation of

his praise and he succeeded, for I was enchanted with the first sight of

this little paradise and half inclined to be angry with G. for having

been able to restrain the expression of his admiration."

From that passage, we see that George Eliot was working during this trip. What might she have been working on? The

Goethe-Handbuch has a single reference to Eliot, in connection with Hans-Richard Brittmacher's entry "Wirkungsgeschichte in der Weltliteratur," specifically English and American literature. Carlyle in his enthusiasm for

Wilhelm Meister, which inspired his own

Sartor Resartus (1838), seems to have inspired the genre of "apprenticeship novels," which included

Contarini Fleming by Benjamin Disraeli and several by Edward Bulwer-Lytton. And, then, Brittmacher writes: "Den Bildungsweg einer weiblichen Heldin stellte George Eliot in

Middlemarch (1871-72) dar."

Eliot's essay concentrates solely on externals. We do not learn in it, for instance, that she and Lewes got to know Franz Liszt, who was then living in Weimar. Moreover, in view of their own relationship, Lizst was living with a married woman, a princess at that, Caroline Sayn-Wittgenstein. Through Lizst they met writers, musicians, poets. They even attended performances in Weimar of Wagner's operas, but were worn out by the second act of

Lohengrin.

The externals of Weimar, as she writes of them, are those one might expect of an English person, very attuned to gardens, town vs. country, and the beauty of the natural environment. Her first impression of Weimar, as she set out exploring the town, was: "How could Goethe live here in this dull, lifeless village? ... [I]t was inconceivable that the stately Jupiter, in a frock coat, so familiar to us all through Rauch's statuettee, could have habitually walked along these rude streets and among these slouching mortals. Not a picturesque bit of building was to be seen; there was no quaintness, nothing to remind one of historical associations, nothing but the most arid prosaism."

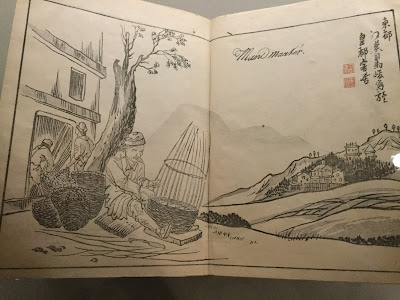

It must be said that, in the course of things, she gives the town and townspeople their just due. For instance, of the market, next to Herder Platz, she writes that it is a cheerful square "made smart by a new Rath-haus. Twice a week it is crowded with stalls and country people; and it is the very pretty custom for the band to play in the balcony of the Rath-haus about twenty minutes every market day to delight the ears of the peasantry." She goes on to describe the head dress worn by local women at the market.

For the most part, however, the outings she describes in the essay concern the more splendid environs of the town. The park on the Ilm, the Belvedere, the Schloss, Oberweimar, Not to forget Goethe's Garden House, which she describes as "a homely sort of cottage such as many an English nobleman's gardener lives in." I couldn't help thinking of

To the Manor Born. I was very impressed that she knew of the "torchlight performance of Goethe's

Die Fischerin in Tiefurt, on the bank of the Ilm, where the river is seen to best advantage. It turns out that the one place associated with Goethe that she most liked was Ilmenau. The essay ends with a laborious walk to the Kickelhahn, where one can see the lines written by Goethe's own hand.

At the start of the essay, when Eliot speaks of her surprise at the homeliness and rusticity of Weimar, I could not help thinking that Goethe, having had a hand in many projects that enhanced the ducal quarters of Weimar, never turned his talents to "town planning." In this era, the "face" of a town was the last thing on the mind of its rulers and administrators. For those who did conscientiously seek to improve the "infrastructure," it was more homely projects, for instance, roads and water supply, that were at the top of the list. So, Weimar became Goethe's "hometown," where he lived for almost fifty years, during which time he occupied important bureaucratic roles. It would be expecting too much for a bourgeois person, which he was, to have concerned himself with the externals of Weimar.