Goethe was never actually in Copenhagen, certainly not in 1932, but it shows the extent of his reach and influence and the general knowledge of his works that a parody on his play Faust was performed in the city in 1932, and by some very smart people at that. It was the 100th anniversary of his death; this is my third post on the commemorations in that year.

Like many of my posts on this blog, the inspiration for this one comes from others, in this case from a new friend, who, learning of my work on Goethe, recommended a book he had liked: Faust in Copenhagen: A Struggle for the Soul of Physics, written by Gino Segrè. Now that I have read the book (struggled through it: the subject is the development of quantum physics in the early 20th century) and done a little research, I see that Faust in Copenhagen was well received on its publication in 2007. It turns out that Copenhagen, through the efforts of Niels Bohr, became a center of theoretical physics in those years, drawing many British and continental physicists. From 1929 until the beginning of World War II, an annual conference was held there. Copenhagen, it turns out, is widely used in connection with a concept called "The Copenhagen Interpretation." Which means? you might ask. According to the Wikipedia link, the term was invented by Werner Heisenberg, one of the featured players in Faust in Copenhagen, to describe the various features of quantum mechanics in the early 20th century.

|

| Bohr, Dirac, Heisenberg |

Already in 1932, of course, there were signs that Europe was traveling in a disturbing direction politically. The physicists at the 1932 Copenhagen conference seemed initially to have been gobsmacked less by the ominous rise of National Socialism than by an important transition in physics. In April 1932, before the gathering, James Chadwick had published his discovery of the neutron ("the proton's neutral counterpart with the nucleus [of the atom]." The neutron, "loaded with mass" had applications that would move physics from theory to experiment, from coal and oil to the "birth of apocalyptic weapons." Thus, in hindsight, the relevance of the bargain Faust made to acquire knowledge of nature and its processes. As Segrè writes, with Chadwick's discovery "the pursuit of knowledge had uncovered a truth with implicit powers for both good and evil."

Okay, it took me three weeks of reading to be able to write the above. "Neutron" and "proton" I have heard of; I am aware that there is a "structure" to the atom. But how about neutrino ("tiny, subatomic particles, often called 'ghost particles,' because they barely react with anything else," but are at the same time "the most common particle in the universe")? That last little bit of the equation was the insight of Wolfgang Pauli.

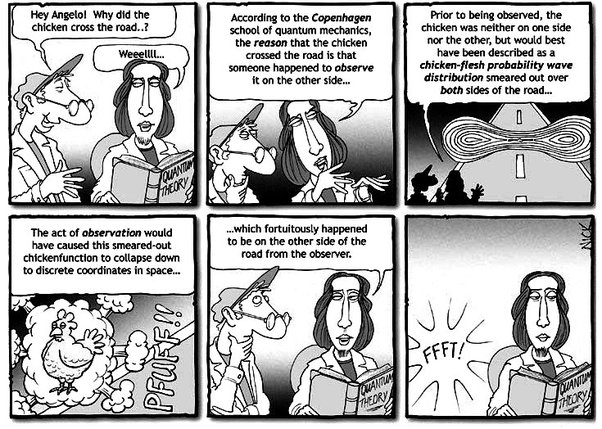

Not all of the great physicists of the day were on board with the Copenhagen Interpretation. E.g., Schrödinger. The cartoon above, portraying him (left) and Heisenberg (right), suggests the different views of "reality." Likewise, Einstein: "I cannot seriously believe in it because the theory is incompatible with the principle that physics is to represent reality in space and time, without spookish long-distance effects." But Einstein clearly had to be incorporated into the Faust parody, and his role was derived from the scene in Auerbach's Cellar in which Mephisto amuses the drinkers with a song about a king who has a giant flee that no one is allowed to touch and which leads to the court's suffering (Faust I, 1880–87). In the Copenhagen skit, Einstein is portrayed as the king, "since his new theories are compared to fleas that torture the king's court." Part of the song Mephisto sings in Copenhagen is as follows:

According to Segrè, the participants in the play in 1932 gathered in the Copenhagen institute's first-floor lecture hall for the performance. Three astrophysicists sitting at a lecture table in the front of the hall stood in for the three archangels in the Prologue of Goethe's Faust who "lauded the Lord for the creation of the heavens." Mephisto then appeared, "sarcastically jibing the Lord for his seriousness: "My pathos soon thy laughter would awake/ Hadst thou the laughing mood not long forsworn" (Faust, Prologue, 35–36).

Many other names in physics in the early half of the 20th century turn up in this account, as the book concerns more than the so-called Copenhagen mecca. Besides Copenhagen, young scholars in the early decades made a Grand Tour of Göttingen, Berlin, Munich, Leipzig, Zurich and Cambridge to consult and work with others in the field of theoretical physics. Enrico Fermi makes an appearance, and also Robert Oppenheimer, whose work in Europe led him to establish two institutes of theoretical physics in California, which in the 1930s "spread the doctrine of quantum mechanics' Copenhagen interpretation." All this shared work and communication among scholars led to what Segrè calls "Big Science." By 1933 it was first realized by Leo Szilard that the potential of chain reaction ("the neutron entering the nucleus to enter it and release two neutrons) would lead to the building of nuclear weapons.

I am afraid I am still unable to provide a picture of what the theory of quantum physics is all about. Maybe the above cartoon helps? I can't help wondering what Goethe would have made of all this. Heisenberg, like most of the scholars portrayed in Faust in Copenhagen, was familiar with Goethe's writings. At a 1967 meeting of the Goethe Society in Weimar he spoke about Goethe's understanding of nature, which arose first with sensory impression and observation of phenomena. Faust's journey begins with his assertion that he is tired of learning. As in many other respects, Goethe was ahead of his time in foreseeing the downside of material progress. In the final scenes of Faust Mephisto murders an aged couple (Philomen and Baucis) living on land that he wishes to clear for improvement. And he does so.